Stanford XCS224U: NLU I In-context Learning, Part 3: Current Moment I Spring 2023

Transcript

Welcome back everyone. This is part three in our series on in-context learning. I've called this part the current moment. That is either foolish or foolhardy or both. The current moment is surely going to change very fast as the field changes. I think I can say that the lessons here will be useful no matter what direction the field takes next.

As always, I want to start with data. Data used for self-supervision. This is an incredibly important ingredient when it comes to understanding the behaviors of our large language models. This is a slide that I used in a previous screencast, but I augmented it with the colossal clean crawled corpus C4.

This is a dataset that was created as part of the T5 modeling effort, and it is audited by Dodge et al 2021. Interesting side note, the Washington Post did an article that is essentially about the dataset and the auditing work that Dodge et al did. They called that article inside the secret list of websites that make AI like chat GPT sound smart.

I'm not sure secret is appropriate here because it seems like everyone is being pretty open about what is in C4. But nonetheless, the article is very useful in terms of helping you, people like us, audit what was in datasets like that. Undoubtedly, the data that are used for unsupervised pre-training are an incredibly important ingredient when it comes to understanding what our models can do and where they're limited.

But as I mentioned at the end of the previous screencast, this is no longer the only ingredient. We have left the era when all of the language model pre-training was simply unsupervised language model pre-training. We have now entered into the era of instruct fine-tuning. Unfortunately, we know much less about what is happening with instruct fine-tuning.

We don't really know what the large industrial labs are doing in terms of data and protocols here. We can infer that they are paying lots of people to generate instruct data. That means that very often these people are doing quite sophisticated things. For example, I think people might be prompted with a text that says, write a certain Python program, and then a human actually writes that Python program.

That's just one instance of many domains and areas of expertise where they have recruited people to exemplify the desired behavior. Again, a reminder that the really sophisticated things that we're seeing from language models these days are not emerging in some magical way from unsupervised pre-training, but rather emerging very directly from standard, good old-fashioned supervision.

I think we can also infer that these large industrial labs are using their own models to generate examples and adjudicate between examples. In fact, we're going to review a method along those lines, self-instruct, in just a second. If you would like to get a feel for what instruct fine-tuning is like, I would encourage you to check out the Stanford Human Preferences dataset.

This is a new release on instruct fine-tuning dataset that was derived from Reddit posts. You could use that, maybe using subparts of it or different protocols for fine-tuning to get a feel for how instruct data affects model behaviors, and that could be quite illuminating. I mentioned self-instruct before. I think this is a powerful method that points to lots of new ways in which we could use models to make models better.

For self-instruct, we begin from 175 tasks that were written by humans. Those go into a task pool, and then we have a language model generate some new instructions via in-context learning. The generated instruction is then fed back into that same language model with a new kind of prompt that helps the model decide whether the instruction is a classification task or some other kind of task.

Depending on the generated response at step 2, we feed the generated output into one or another of these two prompts down here, and that step gives us new input-output pairs that we can use for subsequent supervised language model pre-training. There's some filtering there for quality and to make sure the dataset is diverse, but then those generated instructions go back into the task pool and can participate in parts of these prompts to generate more data.

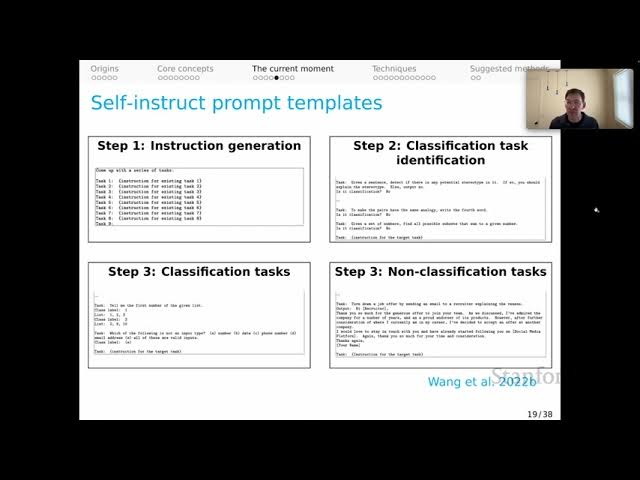

In that way, we can use a language model to bootstrap a new dataset, and then we can update that very same language model with the new dataset in the hopes that that will lead it to have more and more diverse abilities. That was abstract, so let's walk through how self-instruct happens at the level of the prompts that they use.

At step 1, we have instruction generation. This is the prompt. You can see the model is given eight demonstrations and then asked to generate a new instruction. The majority of these demonstrations were human-created, but in subsequent rounds of self-instruct, some of them were actually model-generated instructions. At step 2, we have classification task identification.

The generated response from step 1 is fed into this prompt, and the model learns in context to predict whether or not it was a classification task. Depending on the generated response there, we either feed it into a classification task prompt or a non-classification task prompt. The results here give us new input-output pairs that we can use to augment our self-instruct dataset.

Then as I said, we do subsequent language model supervised, pre-training in the standard way, or maybe with some other techniques to update the model that was used for this generation process. That self-instruct was a major mechanism behind Alpaca. Alpaca was an important recent moment for the field because it started to show people that we could via self-instruct methods, take relatively small models like a seven billion parameter model, do some instruct fine-tuning, and get a very capable result as the output.

In more detail, the way Alpaca works is we begin with a Lama model. Lama is a class of models that was released recently by Meta AI. The Alpaca team began from the 175 tasks that were written by humans for the self-instruct paper. Then they follow self-instruct with some minor simplifications using Text DaVinci 3 as the engine to create the new input-output pairs.

That gives them a dataset ultimately of 52,000 examples, and those examples were used to update the Lama model to create Alpaca. The observation is that the results of this relatively small-scale effort to update the Lama model are actually quite powerful in terms of imbuing Alpaca with new instruct following behaviors.

Again, there's a major lesson there about technology, and I think this is an exciting new direction for the field as we think about making these relatively small models ever more performant. There is also a lesson for you about what's going to be effective for in-context learning because obviously, to the extent that you can tune your own prompts to align with the instruction fine-tuning data that models like Alpaca have seen, you will be more successful, and that lesson generalizes to all of these large language models.

For some, we have visibility into the instruct fine-tuning data as with Alpaca, but for the largest ones, we don't. People have to organically discover which prompting techniques work, which is really a process of uncovering, I believe, what their instruct fine-tuning phase was like at this point. Alpaca, as I said, was exciting because it bucked the trend of model sizes going up, up, up.

This is a slide that I used in the intro lecture for the course. We got all the way up to Palm at 540 billion parameters. It may be that GPT-4 is substantially larger even than that. As a result of this instruct fine-tuning, we're starting to see that model sizes might come down and nonetheless be very performant.

That is incredibly exciting because it's going to happen. There are lots of incentives, intellectual, technological, financial for us to find a way to have smaller models be performant. I think that will be an important step toward actually truly democratizing access to large language models and the capabilities that they can enable.